Book review: Thương Nhớ Thời Bao Cấp, Nha Nam Books and Writers’ Association Publishing House

Nostalgia, satire and education prove a triple threat in Memories of the Subsidized Era

By Michael L. Gray

Two weeks before lunar new year in Hanoi, a book of cartoons about daily life during the war-time years sold out within days of its launch. Memories of air raids, forced conscription and ration tickets hardly seem like subject matter that would put a sentimental smile on people’s faces. But in Hanoi today, nostalgia for the subsidized era of ‘high Communism’ in the 1970s and 80s has crept into the popular imagination.

The hipster socialist-realism décor of Công Café heralded the beginnings of a rethink on the drab khaki palette of Vietnam’s recent past. Hanoi’s digital generation are at least branching out from their fixations with the latest phones and brand-name fashions to learn more about the modest conditions under which their parents and grandparents came of age.

Even so, the sell-out success of Thuong Nho Thoi Bao Cap (Memories of the Subsidized Era) surprised everyone, including the authors. After an initial print run of 5,000 copies was snapped up, a second printing of another 5,000 copies is set to sell out as well.

The book is not merely nostalgia. It took five years to publish due to a long battle with state censors, who pulled out some 20 cartoons before finally granting a printing license. Memories deals directly with the politics of the day by illustrating the stock phrases, idioms, slang and mannerisms of the subsidized era. This is done in an unmistakeably satirical manner, with the authors walking readers through an alphabetically arranged critique of the rampant bureaucracy, nepotism and inefficiency of the times – subject matter that still resonates today.

To ensure the meaning isn’t lost among youthful readers, the authors have included for each illustration a short explanatory paragraph that brings the long-lost historical context or fuzzy linguistic references into sharp relief. So, the book is not only nostalgia and satire – it’s education.

With proper satire, the laughter is not in the punchline so much as in shining a humorous light on an unfortunate underlying ailment. While this discovery of the “unvarnished truth” may be slowed somewhat for readers who need the help of the book’s guideline paragraphs, many of the political cartoons are simple enough to understand at first glance.

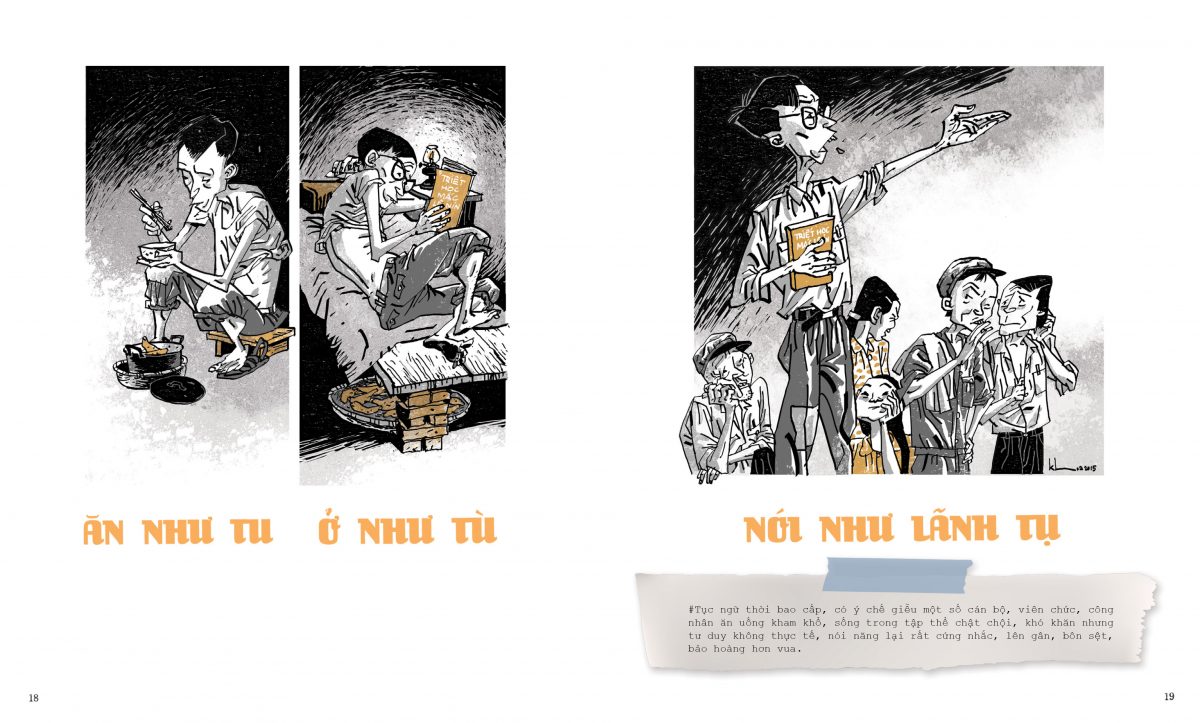

“Eat like a monk, live like a prisoner, but speak like a leader”

Before they had enough spare cash for Rolexes and Gucci suits, many cadres lived in dire conditions. Nonetheless, as the explanatory paragraph below this cartoon points out, their common-man living conditions didn’t prevent them from rigid minds and words, not to mention ‘being more royal than the king.’

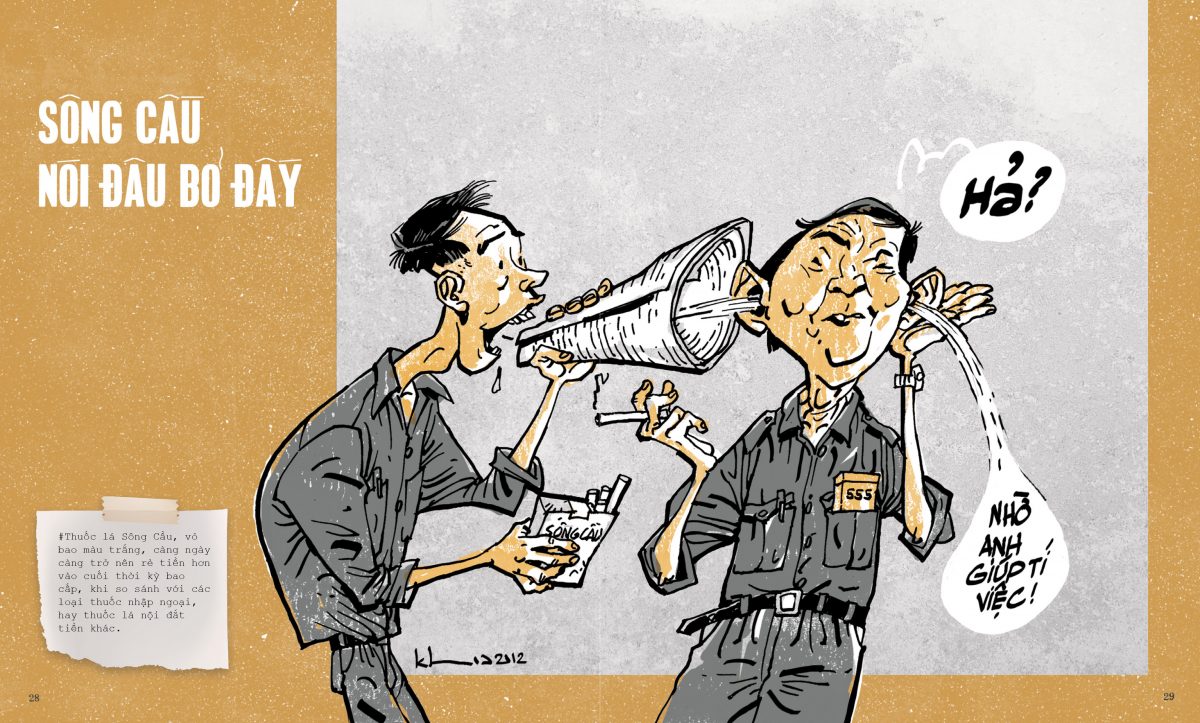

Several idioms refer to particular brands of cigarettes, which were key items to procure assistance from low-level bureaucrats. Here, local ‘Song Cau’ cigarettes are not sufficient to bribe an official, who clearly wants a pack of imported 555s before offering help. While the importance of cigarettes as transactional grease has faded, even pre-drinking-age youth in Vietnam likely know the difference between gold- and red-labeled bottles of Johnny Walker.

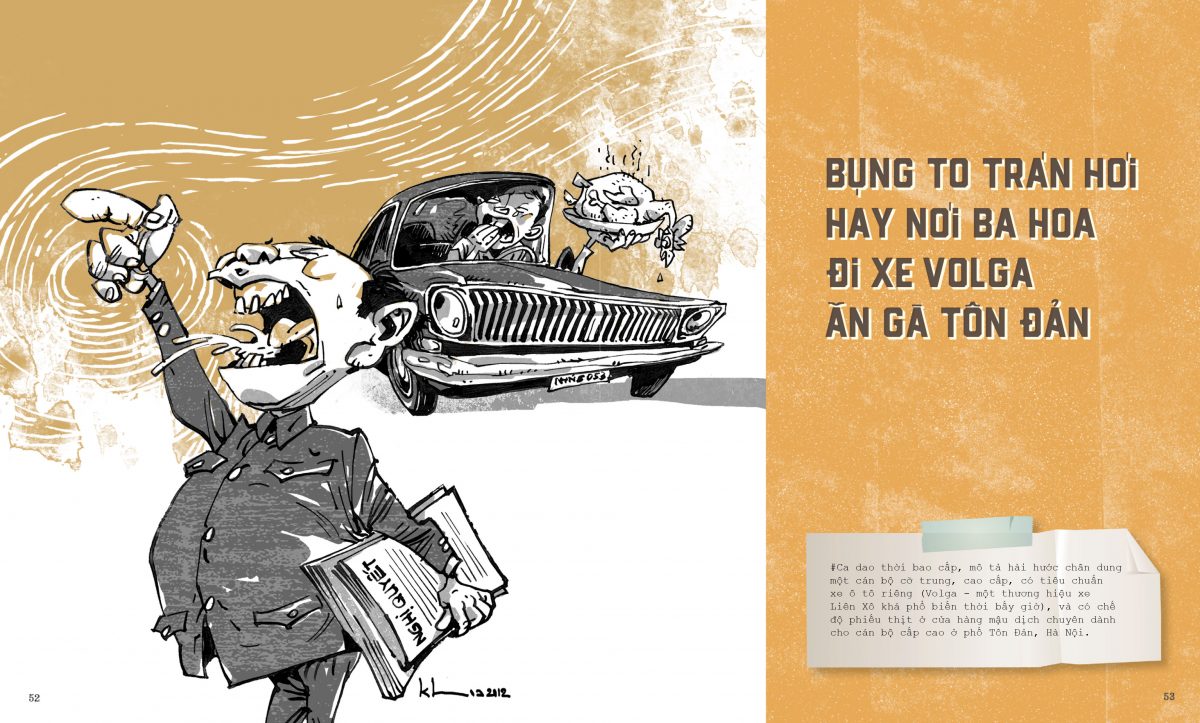

“A big belly and a bald head means they ride in a Volga and eat chicken from Ton Dan”

Fat-cat bureaucrats require no explanation, but most readers today will need the footnote to learn that a Volga was a Russian saloon car and Ton Dan was the street that housed the luxury goods shop reserved for high-level cadres. The spittle and broken teeth no doubt made this mockery of officialdom a cause for concern among the censors.

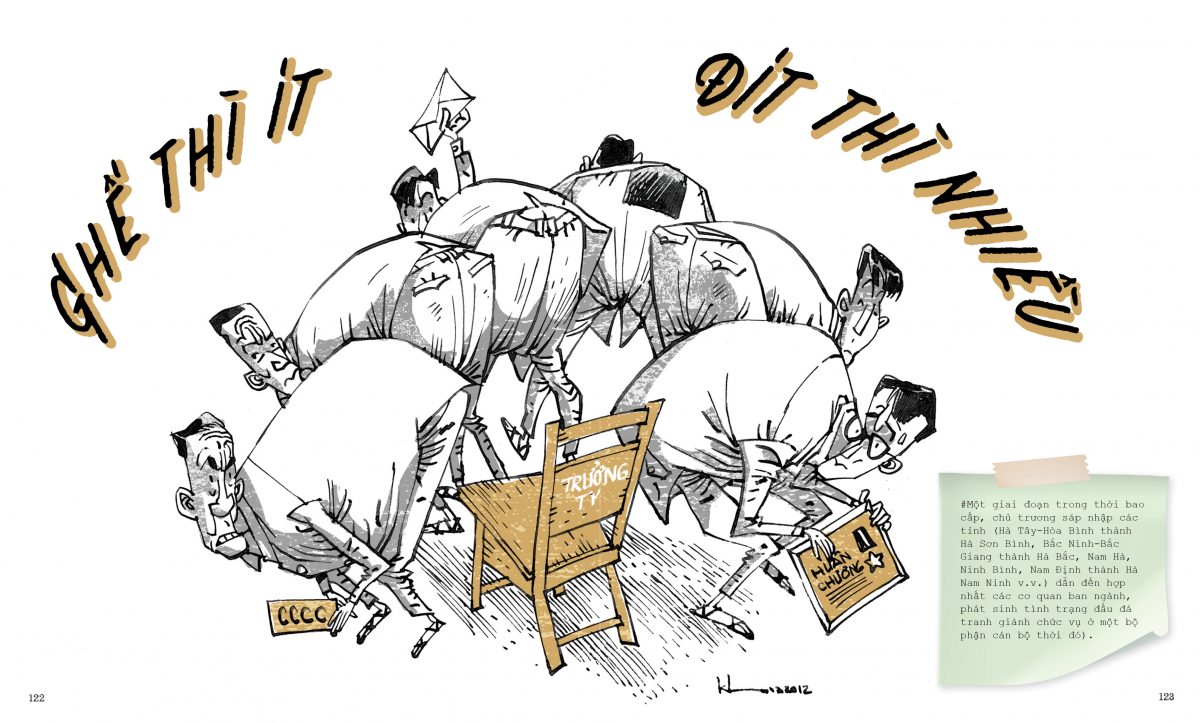

“Not enough chairs for too many asses” is simple enough to understand, but the footnote makes it clear the saying originated from the time when many provinces were being split into two – effectively doubling the number of rent-seeking administrators serving the same number of people.

The book is not all politics. Ribald humor begins with the very first cartoon, which shows two women speaking in front of an artillery cannon. “Don’t marry an artillery gunner,” one woman cautions, “every night they shoot hard enough to shake the bed.”

Modern readers may be unfamiliar with ration tickets, but will still recognize the fatalism of a cartoon depicting people waiting in a food queue even as rockets fire overhead. The caption reads: “Whoever goes to heaven will go, I’m staying in line.” (It doesn’t take much imagination to write a modern parallel: “Whoever dies in traffic will die, I still need to get from A to B”).

The book’s occasionally raucous humor seems to have drawn the ire of censors in equal measure to its political content. On his Facebook page, author Thanh Phong posted a cartoon that was among those pulled from the book by censors. It’s little more than a fart joke, the humor lying in the fact that someone could smell meat in the fart’s particular odor (at a time when the nation was so poor that meat was a luxury). The cartoon emphasizes the extreme poverty of the day, but is otherwise bland compared to the mocking tone of several that made it through to the printing press. The censors don’t justify their decisions, and operate with a set of concerns not made public nor explained to the authors.

Thanh Phong and Huu Khoa began the Memories project in 2012 when they were staff members at Nha Nam, founded in 2005 as one of the first private sector book publishers in Vietnam. Nha Nam wanted to introduce Vietnamese illustrations into a market otherwise dominated by translated Japanese manga. This effort started with Thanh Phong’s first book of cartoons, Assassin with a Head of Festering Wounds, which was a huge success in terms of the critical and social media attention it received. The book was a series of illustrated modern slang and idioms (broadly similar to Memories). Assassin gained notoriety when, two weeks after release, all copies were withdrawn from bookstore shelves and disappeared, to reappear weeks later with several pages cut out (most notably a cartoon of two soldiers playing hacky-sack with a hand grenade).

Thanh Phong is an artist willing to balance on the edge of permissible content. But in Memories, it’s not his work that stands out. Born in 1986, he’s too young to remember pre-doi moi times, before the country’s economic opening, and so has relied on interviews, photographs and other research to fuel his imagination. Huu Khoa, born in 1973, is in his element. His work dominates the book both in quantity and quality. All the examples in this review are Huu Khoa’s illustrations.

Huu Khoa’s caricatures have wonderfully expressive faces, bringing great depth and emotion to his cartoons. The quality of the artwork, including Thanh Phong’s, is excellent.

Nonetheless, a critical perspective on Memories is that satire isn’t as effective when presented so long after the fact. While many of the cartoons would have seen the authors tossed in prison if published in the 1970s or 80s, they’re harmless compared with much of the anti-state vitriol now available to anyone with an internet connection.

The official approval denoted by a publication licence means there’s nothing in the book to shake the foundations of Vietnamese society. But it would be too much to expect Vietnamese satirists, working under the gaze of an authoritarian regime, to attempt the open mocking of contemporary leaders seen in Hebdo or on The Daily Show.

Memories is an effective twist on the propaganda of nationalistic patriotism and sacrifice that dominates discussion of the wartime years. In one of the book’s cartoons, the phrase ‘worried about the country’ is transformed to mean ‘worried about water’ – as the illustration shows neighbours lined up to collect their meager daily bucket of water from the communal tap.

Even today, government agencies blend propaganda into media and entertainment productions in a manner far less effective than they imagine. In its revisionist look at the stock phrases and nation-building slogans of the recent past, the book exposes the anaemic core of much of the propaganda/entertainment produced in Vietnam. This is a type of critical education that youth don’t receive in secondary school classes. As a work effectively combining nostalgia, satire and education, Memories of the Subsidized Era is a triple threat.

This review was first published in the May 2018 edition of Mekong Review.

I had the address written on a piece of paper. 79 Ly Thuong Kiet Street.

A visit from a man who claimed he was robbed at gunpoint and his secret documents stolen.

Richard Pettit was the Charles Bukowski of Hanoi in the late 1990s. This is one of his stories.

© 2017 Michael L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy