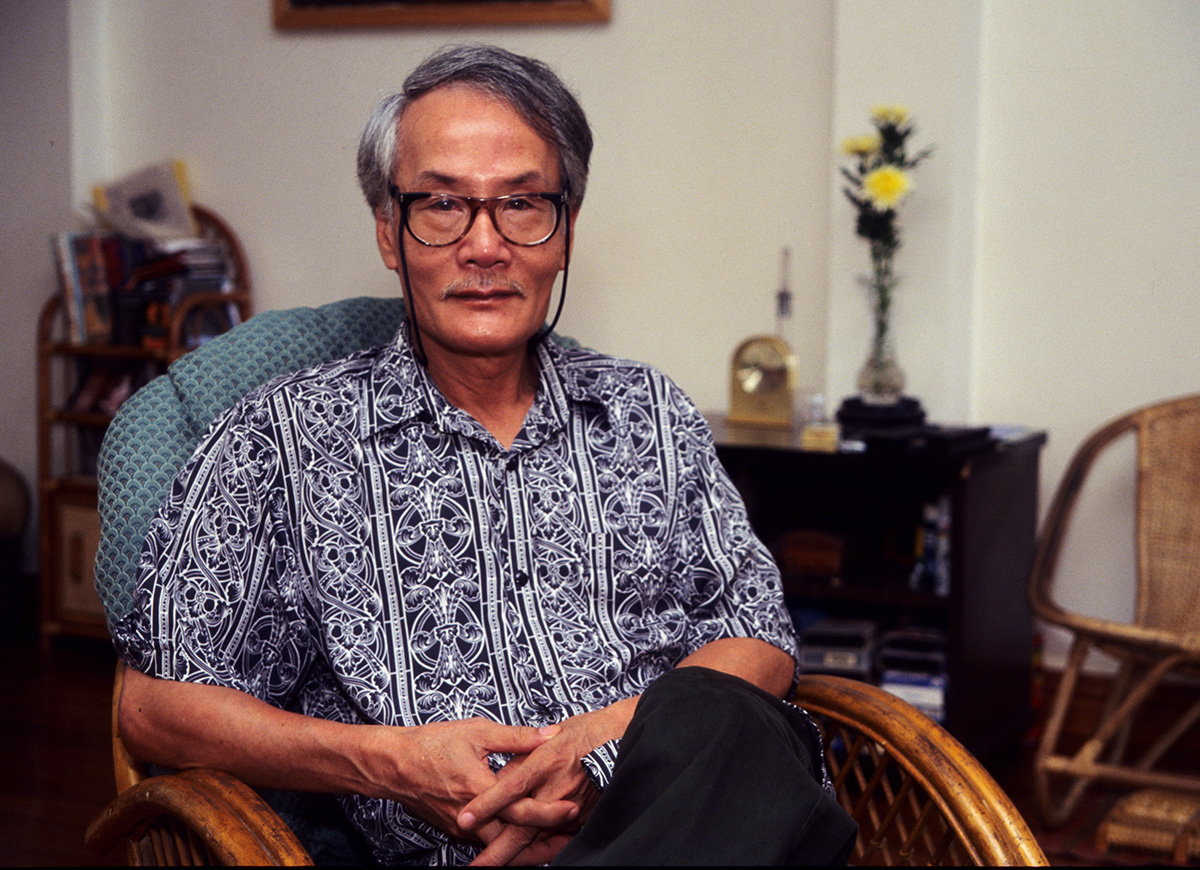

Mr Nguyen Khuyen in 2001.

1.

I had the address written on a piece of paper. 79 Ly Thuong Kiet Street. An Ottawa neighbor had called a few days before I left for Hanoi. She told me a friend of hers had worked at the Vietnam News, and I should give them a call. So when I found myself walking down Ly Thuong Kiet Street with a friend, I suggested we stop for a few moments at the office. We were on our way to the United Nations compound, which was just across the street.

There was a plaque on the gate. Vietnam News, national English daily of the Vietnam News Agency. The gate led to a parking space covered by a large arch of bright blue plastic. The building was at the back. We walked up to the second floor, and my friend waited outside when I went into the office. There were four young women sitting behind a desk near the door. The office was one big room, with people milling about everywhere. There were a few foreigners off to one side.

‘Can I talk to the editor, please?’ I asked.

One of the girls dashed off, while the others sat there, staring at me. I was wearing white linen pants, a cream-colored shirt, and my hair was cropped close to my skull. I had three gold hoops in my ears. I am six feet tall, and very thin. My skin is pale at the best of times. I looked down into three unblinking pairs of eyes. I smiled to be polite, and they all smiled back in unison. One of the women, Thuy Quynh, later told me, ‘at this moment, I thought you were a ghost.’ I was led to the back of the office, and told to sit at a small rattan lounge. Soon an older Vietnamese man came over. He poured some tea as he introduced himself.

‘I am Mr. Khuyen,’ he said. ‘How can I help you?’

This was the editor. He was a striking character. He was small and thin, but silver hair and bronzed skin gave him a very dignified look. He wore a loose silk shirt cut in Chinese fashion, with baggy pants and plastic sandals. He was handsome, but had a sharp cut to his jaw that gave him a stern look. It was clear he was no one’s fool. His English was superb.

I explained who I was: a Canadian student living in Vietnam for a year, looking for work. I said I would be traveling to Ho Chi Minh City, and would return to Hanoi in one month.

‘How can you help the paper?’ he asked.

I stumbled on this a bit, but said my writing was decent, so I might be able to help as a writer or proofreader.

‘Yes, there might be work for you here, but perhaps part-time at first. Call me when you get back in one month.’

With that, he excused himself, and I took my leave. My friend, a fellow student, was waiting for me in the hallway.

‘So?’

‘Yeah, looks alright. He said to call him again in a month.’

We walked back outside and soon came across the UN compound. It was the last week of May, 1995. I was less than one month removed from life as a university student in Montreal.

2.

When I arrived back from Saigon, in early July, I went to the Vietnam News office right away. I met Mr. Khuyen again and he asked me to start the next day, working part-time. My life as a cadre had begun. I was a subeditor at the Vietnam News, English-language daily of the Vietnam News Agency, the press agency of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The newspaper office was one big, long room, with no partitions. A corridor overlooking a courtyard ran parallel with the office. You could look into the office from a series of windows along the corridor. Desks were arranged haphazardly throughout the room. At the far end, Mr. Khuyen had a small desk facing into the office. Next to his desk there was a rattan lounge set where he could welcome guests. Close to Khuyen’s desk, in the middle of the room, was a bank of six computers arranged in a square. This was where the layout was done at night. Beyond the row of computers were several desks where most of the young staff worked. Finally, at the end of the room, the older staff members huddled together. Khuyen’s wife, Hue, occupied one corner. Several of the older staff did not appear to have any actual work to do. One man in particular just sat there with a scowl on his face all day, his hands folded in front of him, doing absolutely nothing.

Two very old men worked quietly at the back of the office. They were proofreaders, although they did not contribute much to the actual work of improving stories. I think everyone thought they were very quaint. One of the men would come up to me when he had a question and say, ‘Please, sir, can I ask you…’ before pointing out a possible error in grammar or syntax. His age probably tripled mine. Even after I learned some Vietnamese, he still spoke to me in French. He looked like a neighborhood grandpa, wearing pyjamas and plastic flip flops, with a cardigan sweater over top. He almost always wore a scarf or hat, even in the summer. He was very poor, apparently, as he did not even own a bicycle, and walked halfway across Hanoi to get to work. Both of the old men at the back of the room were schoolmates of Khuyen, and he was making sure they got by. Only on occasion did they spot an error, but they had been students of English since the 1950s and their knowledge of grammar was impressive.

Sitting in small groups scattered throughout the office were the young translators, most of whom were women. There were about fifteen or so, and it took me quite a while to remember all their names. I settled at a desk next to Phuong and Thuy Quynh. We spent almost as much time talking as we did working. They were both very inquisitive and sweet natured, and I enjoyed their company immensely. They were my introduction to life in Hanoi and to Vietnamese culture more generally (and they remain, twenty years later, dear friends). They translated stories and gave them to me to edit. Their spoken English was very good, but their writing was fairly basic. Like all their colleagues, Phuong and Thuy Quynh translated directly from Vietnamese. They wrote ‘pig meat’ instead of pork. The language was always passive and ‘backwards’ in the sense that Western news stories start with the most important facts at the beginning. In Vietnamese papers, anything new or important is normally buried at the end. But at first I knew very little about how to structure news and feature articles, so I mostly just fixed the grammar and went on to the next story.

The front page of the newspaper was always diplomatic news and the daily speeches or activities of the leading triumvirate – the prime minister, the state president, and the general secretary of the Communist Party. We had no choice in this, as the Vietnam News Agency required the paper to follow protocol in the order stories were reported. The entire front page was therefore full of terrible diplomatic jargon and hackneyed phrases. Every single diplomatic visitor was ‘greatly appreciated’ for whatever assistance they gave to Vietnam. It didn’t matter whether it was for moral support during the war, or technical assistance to aid national reconstruction. Polish scholarships provided in the 1980s were greatly appreciated, as were Japanese loans to build a new airport. And we eventually had to accept that Vietnam had a strong relationship with almost every country in the world ‘based on mutual understanding, friendship and cooperation.’ I saw this phrase appear, literally, about every second day for my entire time at the paper.

After the first page, the next few pages also dealt with national news. This mostly consisted of endless reports on investment and production statistics. There was no investment project, foreign or domestic, too small to escape the attention of the Vietnam News. We reported extensively about investment in roads, buildings, textile companies, boats, shrimp canning factories, pigs, motorcycle assembly lines, hotels, mini-hotels, new rice strains, fruit trees, coffee… the list went on and on. And everything was always ‘up.’ Rice production up six percent on last year, textile production up 12 percent on the last quarter. Nothing was ever down, unless it was meant to be down. Poverty and illiteracy were always down, but this was good.

There was a lot of economic jargon to cope with. The phrase ‘master plan’ was one that bothered me. I tried using ‘development plan,’ ‘economic plan,’ or just plain ‘plan,’ but not everyone agreed with me. The foreign staff argued all the time about proper English usage. We had on staff people from England, America, Canada, Australia and India. Even after we settled on ‘the Queen’s English’ (to Steve’s great delight) there were still arguments. Hari and Paul would have the most furious and vocal disputes. Our style guide, initiated by Paul, was revised, and revised again. Through all of this, the local staff went about their business of translating ‘pig meat’ and ‘greatly appreciated,’ either oblivious or simply uninterested in our debates.

‘What does this mean?’ I once asked Phuong, pointing to a phrase she had written that defied all logic.

‘That is for our readers to understand for themselves!’ she said in a huff, then stomped off (insomuch as a forty-kilo women can stomp).

This attitude was typical. After a while, it was apparent that my Vietnamese colleagues were not learning from their mistakes. Even after I changed pig meat to pork a dozen times, it still came to me uncorrected. The translators were perfectly intelligent people, but they had little motivation to improve. Their jobs were secure regardless, their salaries were not about to increase if they worked harder, and it seemed as if no one wanted to attract attention by working too hard or taking undue initiative. The Vietnam News was not unique – this attitude prevailed at state offices across the country.

3.

Not all of the editing work at the paper was fixing translations. There were a few international contributors to contend with as well. Khuyen’s editorial outlook when it came to foreign writers was flexible, if perhaps overly lenient. Unfortunately, regular contributions from writers such as Anh Le and Ted Dragin were nothing more than eye-rolling material for the foreign subeditors at the paper. Our view was that Khuyen was happy to print any positive reflection on Vietnamese culture and people – and it was always possible to find Westerners willing to heap platitudes on Vietnam and its people.

Only one regular contributor seemed willing to challenge Khuyen on his editorial approach. Jim Monan wrote a weekly column called ‘Sportingly Yours.’ He was a big, bald Scotsman who boasted many of the features his countrymen are known for – a short fuse, a big heart and a taste for lager. Jim was a consultant for numerous development agencies, and involved in land mine research in Vietnam and the effort to get land mines banned internationally. He introduced me to my first Vietnamese teacher. He made sure she charged me at a rate I could afford. ‘He is a very stubborn man,’ she said. Jim was older than Khuyen, and this combined with his very direct manner of speaking enabled him to say things to our boss that no one else would dare. ‘Khuyen, the Sunday issue reads like a fucking airline magazine,’ Steve overhead Jim say one Monday morning in his thick Glaswegian accent. He had with him a few copies of the Guardian Weekly, which he put in a binder and left at the office. ‘I want the staff to see what a real newspaper looks like,’ he grumbled.

Slowly, Khuyen allowed some ‘letters to the editor’ with subtle or polite criticisms of government policy or Vietnamese cultural tendencies. Many related to overpricing or surcharges given to foreigners above the price Vietnamese paid. Khuyen relied on us to draft responses to these letters, and when no letters arrived, he sometimes asked us to pen letters under pseudonyms. This soon devolved into subeditors penning rebuttals to letters written by other subeditors, which worsened the state of our somewhat incessant infighting. We dropped the practice after a few short months.

4.

I had dinner almost every night at the same com bui. It was an old, run-down stall on Phan Boi Chau street, a short walk from the office. Com bui means ‘dusty rice,’ and this establishment exemplified its genre. It was dirty and neglected. The food sat on a ledge facing the street, behind which perched an overweight woman who always wore cheap, white makeup. Inside, there were four blue plastic tables that stood about two feet high, and a number of tiny stools – some plastic and others hammered together from broken pieces of wood. I would order my tofu and chicken and boiled cabbage, dip it all in fish sauce and munch it down with a bowl of rice. Along with a small bottle of soda, the meal would come to about 8,000 dong (about 75 cents). My lunch was a similar affair. With a coffee and snack somewhere in the middle of the afternoon, I was getting by on about $3 a day. But even with a few evenings a week teaching English, I was barely making enough to cover my living costs.

By February, the coldest month of the year, I was spending more time with my other Western colleagues – Paul, Eric and Steve. My Vietnamese language skills had progressed very little, and I was beginning to appreciate how hard it would be to work long-term in Vietnam. The peculiar assortment of people in the office was no longer just a source of wonder and amusement to me. I found that despite their different viewpoints I had a lot to learn from my Western colleagues. I came to understand how seriously they took the task of learning about Vietnamese culture, and how well they fit in. Most had an educational background similar to mine, but unlike me they knew how to learn from everyday life, particularly life in the street. They didn’t require a classroom, as I did. When we went for beers at local drinking stalls late at night after work, I was just an observer. Paul and Eric, with their language skills, were active participants, accepted by the street urchins we kept company with as an integral part of the scenery. People felt relaxed around them, and they made many friends. They also helped create a working environment that was different from many other multicultural offices in Hanoi. People who worked at the Vietnam Investment Review, a weekly paper, told me foreigners there sat on one side of the office, Vietnamese on the other. None of the expats at the Vietnam News would have accepted such an arrangement. In this respect we were all alike. But for all my lessons in cultural anthropology and politics, I was failing to connect with Vietnamese people in the same way they were. I knew I would have to confront this shortcoming eventually, but I still planned on returning to school to study for a PhD. At least now I knew school wouldn’t teach me everything. Also, as we learned more about Vietnam, we shared our stories and realized we all had a strange mix of sincere respect and benign ridicule for the culture surrounding us. We occasionally made fun of what we saw, but always in a way that betrayed a fondness and appreciation for the fact that things were so different from ‘back home.’ (Steve once wrote an editorial regretting the demise of a Soviet-style collective store that was being torn down to make way for a new business center. He wrote about the beautiful old building: ‘It was a temple for the terminally austere. Bearded men in sandals would feel a welcome release from the pressures of Western consumerism. There were no concessions here. No pandering to the whim of the customer. If you needed a bike, then there it was, a large one or a small one, the choice was yours.’)

I had more in common with my colleagues than I originally recognized. Much later, Paul wrote to me about what he called, ‘the strange, muddled dream we all had when we were still starry-eyed and full of passion for living and working in Vietnam. We weren’t just a bunch of “less arrogant/more understanding” expats but something else, in-betweeners, living in the twilight zone where expat and local worlds and values collided.’

One night, near the end of the year, Paul suggested we split the cost of sandwich ingredients. The paper had recently expanded to 16 pages, so there was more work than ever. We were still working until 11:00 pm every night. We all chipped in some money, and Paul went off to the canned food stores on Phan Boi Chau and Hai Ba Trung, just past my com bui. He came back with some puffy white bread, tomatoes, Dutch cheese and a package of ham. The main capital outlay on this first occasion was a supply of mustard and mayonnaise. These were expensive, but we looked at them as long-term investments. The five of us gathered around a table at the back of the office and slathered our bread with all this wonderful stuff. We invited our Vietnamese colleagues to join in, but they only looked on with amusement. A few wrinkled their noses at the cheese.

Thus was born a long-lasting tradition of eating dinner at the office. From these humble beginnings, Steve and I went on in 1998 to wonderful meals of Indian, Chinese and Italian cuisine. By then we had a small collection of take-out menus carefully stashed away in a drawer. But we never forgot our roots in the humble sandwich; along with Paul and Eric, huddled over a can of mustard and a loaf of squishy bread. These were great, unspoken moments of bonding between a few Western boys of limited means, surrounded by nothing but noodles and rice.

5.

As the end of my first year in Vietnam approached, I grew wistful that my days at the Vietnam News were coming to an end. Mr. K, as we now called him, threw a small party for me during my last week at work, and I had a photo taken of the two of us, standing by his small desk. I knew I would miss my colleagues, Vietnamese and expatriates alike. I didn’t imagine I would ever again work in an office with the same incredible mix of people, including, I must admit, any number of beautiful young women. There were no deskmates like Phuong and Thuy Quynh to be found back in Canada. The exploits of Paul, Eric and Steve had become like a recurring soap opera I didn’t want to turn off. On my birthday, a few days before I left the country, the guys told me to take the night off. I went to the bar across the street from the office and got very drunk. It was a good remedy for the mixed emotions I had leaving the country. Later in the evening, well into a stupor, I told Paul and the guys they were doing the right thing working for a Vietnamese organization, living close to the people, rather than pushing paper for some Western company. ‘Don’t sell out,’ I told them. This was easy for me to say – I was leaving. Altogether the wistful feeling lasted about a week. It was an interesting and valuable experience for me, but working at the Vietnam News was a bad job, plain and simple. It had nothing to do with what I expected to accomplish in my career in international development. I had no thoughts of ever returning.

6.

I returned to the Vietnam News at the end of March 1998, after an absence of nearly two years. After finishing my graduate degree in London I was turned down for a job as a research assistant in Hanoi. Then I failed to get a scholarship from the Australian National University in Canberra. I was left with few options. I sent a letter to Khuyen and called him from Ottawa. I asked if I could return to the Vietnam News for a short time, about six months. He agreed immediately, and told me to come in on a tourist visa, after which he would arrange a work visa. I made plans to return to Vietnam. I was not thrilled about returning to the Vietnam News, but secretly I planned only to stay for a few months. As soon as I got to Hanoi I would begin looking for NGO work, and I didn’t think this would pose much of a challenge.

For the most part, the staff had not changed. Several of the young women were now married, and my two deskmates from 1995 – Phuong and Thuy Quynh – were pregnant. Among the foreigners, Hari, Terry, Steve and Charlie were still there. Paul’s last day of work was a few days after I arrived. Eric had left several months before, but was still in Hanoi working at another paper. Jim Monan of ‘Sportingly Yours’ was still in town. All in all, not much had changed. After a week to settle in, I started work in early April.

The main change at the paper was that John Loizou was now the unofficial senior subeditor. John was an older journalist from Australia who left a major editorial position to come to Vietnam and help develop the English language media. John had a long history of working in Asia and an equally long-held commitment to Communism. He was a member of the Australian Communist Party for many years before it folded. In 1995, John had worked mainly at the Saigon office. In his few short trips to Hanoi at that time, he quickly made an impact on the paper by tidying up the language and making it more professional. I had liked John at first for his gruff manner – like an angry teddy bear – but when I worked with him in 1998 it became apparent that he was a troubled person, and very difficult to deal with.

Terry’s role had diminished somewhat as he prepared for a six-month return to Australia. John was almost the complete opposite of Terry: ill-tempered to the point of belligerence, especially after he returned to the office in the evenings after a few drinks. There were several unpleasant scenes, and he argued with me openly on at least two occasions. Normally Hari received the worst of John’s outbursts (which Hari would return in equal measure). Thankfully, John trusted Steve and I much more than the other foreign staff. Only we were allowed to write headlines, which were faxed to Khuyen’s house for a final check. Steve, with his calm temper, handled John’s mood swings very well. I was less successful with this, and I could see right away that problems were inevitable. I was happy to see all my colleagues again, but I no longer had the patience needed to work at a state organization. I wanted out immediately, and felt guilty that my heart was no longer in it, while others were trying so hard to make the paper a success.

7.

The newspaper had improved in my two-year absence, but it was still based on translations from Vietnam’s state newspapers, with little original reporting. I found it stifling, given my intention of finding work with Vietnam’s emerging non-government sector on political issues like land rights. In the months after my return, it was my colleague Stephen Boyle who kept my mood up. My fellow subeditor had a great sense of humor, and we always found pleasure in the small details that made life in Hanoi interesting. For example, we found no end of amusement in the fact that the Hanoi information telephone line, 108, was the most competent of all state-run agencies. The operators were very professional, spoke decent English, and they did a lot more than find city addresses and phone numbers.

Steve was in charge of compiling a twice-weekly column called Dragon Tales. The column, started by Terry Hartney, was a mix of funny stories and gossip, all very light natured. During the first round of the World Cup in 1998, Linh told Steve she had a funny story for Dragon Tales about her grandmother’s take on a football player from the Nigerian squad. When the strong Nigerian team was demolishing one of their first round opponents, Linh’s grandmother remarked of Nigeria’s striker, ‘Hey, that guy with green hair is pretty good – almost as good as Huynh Duc.’

Grandma was referring to Vietnam’s star footballer, who played for a team called Hanoi Army. We laughed for a good while over this, as anyone who knows anything about international football can tell you that all 11 players who start for Nigeria have a great deal more talent than Vietnam’s top striker. Steve wanted to use this story for Dragon Tales, but we needed to know the name of the player. All we knew was that he had a neon-green weave in his hair. So Steve sent Nam to the phone, to call 108 and ask for the name of the green-haired Nigerian. Nam came back a minute later with the right name: Tarebo West. I asked which club he played for in Europe, but Nam had not inquired about this detail, so we sent him back to the phone. Again Nam returned with an answer in under a minute: Inter Milan, one of the best football teams in Europe.

So Steve and I were in good spirits for the rest of the afternoon, alternately laughing at the grandmother’s overzealous opinion of Huynh Duc’s talents, and the fact that 108 was a better source of information than the Vietnam News (keep in mind that internet access was new and uncommon across Vietnam at this time). But unfortunately there were only a few moments when I had the ability to laugh at my predicament. The daily stress of working for a state media agency was becoming too much to bear. Every day I was asked to edit the news briefs, which were endless and repetitive reports of investment statistics, production statistics, health statistics and literacy rates. I read continually that 100-percent of the population in such-and-such mountainous communes were now literate, when I knew perfectly well there were thousands of ethnic minority women all over the country who spoke not a word of Vietnamese, let alone knew how to read or write. As the months dragged on, I began to lose hope that I would find work that could get me out of Hanoi to learn more about the countryside. Several job possibilities fell through. I began to question why I was staying in Vietnam. As I mulled these thoughts, I had to keep a smile on my face and refrain from showing my Vietnamese colleagues how unhappy I was. It was a struggle.

8.

The seventh anniversary party of the Vietnam News was held in June 1998. It fell on a hot Saturday morning. The previous day, Binh, our chief of staff, told us all to wear neckties. The party would be a fancy affair at the Meritus, a new hotel in the north end of Hanoi, near West Lake. When Hari refused to wear a tie, Binh immediately grew annoyed. He didn’t want us to take this event too lightly. Hari assured him his Indian formal wear did not require a necktie. The problem for me, when I woke up that Saturday morning, was three-fold. First, there was no power, and I needed electricity to iron my clothes. There was no hope of looking presentable without fresh clothes. Second, my head was pounding, the result of a late night on the town. Finally, there was the party itself, a celebration that would be tinged by the frustration I felt in working for the Vietnam News.

There was no hum from the air conditioning unit above the bathroom door. I was already sweating. My only decent clothes were still hanging wet on the line. My head would not stop pounding. I lay in the heat for an hour, and still the power did not come back on. Finally, at 10:30, I sat up and waited on the edge of the bed until my stomach settled. I was annoyed with myself at this point, because a crippling hangover was not going to help me get through the anniversary party. The night before I had finished work as usual at about 9:30 pm. Throughout 1998, my friends gathered on Friday nights at a bar on Hang Dieu street in Hanoi’s old quarter. The bar was open to the street, with a small air-conditioned room at the back. They had a stereo and my roommate would bring his own CDs. When I arrived, two of my friends were sitting at the bar outside. Others were gathered inside, but we stayed out in the heat and started ordering rounds. Eric Thiel soon showed up, and as he was now employed at another paper we often spent Friday nights complaining about our work – the sort of open dissent we couldn’t show to our Vietnamese colleagues. On this night the beers flowed and flowed and the conversation grew increasingly exuberant. We never made it into the back room to join the rest of our friends. They emerged at 2:00 am, after the woman who ran the bar finally closed shop.

Rather than head home, we continued on to another bar and it wasn’t until around 3:00 am that I finally called it a night. The next morning, my head would not clear and my stomach would not settle. Even a shower didn’t help much. The power did not come back and I gave up on the hope of ironing my clothes. I pulled on the pair of pants I had worn the night before, still stinking of smoke. At least the shirt was clean. I put on a tie, and in the end looked fairly presentable. I had to cycle north clear across town to West Lake, the posh end of Hanoi. By the time I arrived at the Meritus I was soaked with sweat again. It was now noon, and the heat was unbearable. The Meritus had a huge lobby and piano bar. The central feature of the lobby was an escalator leading to the second floor ballroom. It was Hanoi’s first escalator, perhaps the first in all Vietnam. In such a fancy hotel lobby it looked ridiculous, especially the bright yellow safety stripe on each step. But there’s no arguing with progress and the beast was running, so I hopped on. I entered the ballroom thirty minutes late. Over 100 people were already seated and some tables had been served food. I scampered around and found a seat next to Binh, the chief of staff, and Phuc, who filled in for our chief editor one night a week.

‘Why so late?’ Phuc asked immediately.

I was too hung over to speak Vietnamese, so I replied in English that my house had no power, and I had to wait for my clothes to dry as I couldn’t iron them.

‘You’re not as clever as me,’ Binh laughed, ‘I just bought a new shirt and left it in the pack until today… Hey bring another cup of wine!’ he called to a waitress, almost interrupting himself.

I knew this wine would be for me, but I did not have the energy to protest. I looked around but recognized none of the others seated at my table. They were not Vietnam News staff. I knew they must work for the Vietnam News Agency, the main umbrella organization for the media in Vietnam, our paper included. In Vietnamese I asked the man next to me what he did at VNA. ‘Driver,’ he answered in English. This was not the reply I was expecting, and I had nothing to add. Luckily the food started to arrive at our table. It looked quite good. Chicken fried with chillies and peanuts was the first dish. I waited until the others served themselves before filling my bowl.

By the time we began eating, Khuyen was making the rounds with a bottle of whiskey to toast the paper’s success. He was obviously very happy the paper was making enough money to pay for a party like this. Khuyen was set to retire in one or two more years, and changes were soon expected at the paper. There was a merger planned between the Vietnam News and some relic called the Courier, with one by-product being that VNA would take much closer control of the paper. Until now Khuyen had been firmly in charge, and while the paper was hardly top-notch, at least a lot of money had been made.

Khuyen arrived at our table and immediately inquired why we didn’t all have whiskeys yet. A waiter was following close behind with a bottle of Black Label and a tray of glasses.

‘Sir, I really don’t need that now,’ I pleaded when a lowball started heading my way. I grabbed the glass of wine in front of me and Mr. K seemed satisfied with this. I didn’t need the wine either, but I figured it would do less damage. We all toasted the paper and Khuyen moved on to the next table. I ate a bit more, but nothing was happening at my table. Binh and Phuc soon got up themselves, so I began to look around the hall for another seat.

My first destination was the opposite side of the ballroom were most of the younger foreign staff were seated. I thought their table would be a good place to hide for a while, as they likely had hangovers as well and so would understand my predicament. Also seated with them was Van Anh, one of the young translators, and Mrs. Hue, the editor’s wife. I greeted Hue first, then all the proofreaders. I also said hello to Van Anh, who looked stunning in a blue and white ao dai. I taught her and her friends English the first year I was in Vietnam, and she started working at the paper a few months after I met her. Although she had matured somewhat in my two years away from Hanoi, she was still extremely shy and conservative.

‘Are you drunk?’ she asked, showing great concern.

I told her I was just tired, which was very much the truth.

‘I only had half a cup of wine,’ I protested, not mentioning the previous night’s over-consumption.

There were no empty seats at the table, so I headed to the back of the room where My Ha and Hai Van were seated. My Ha was the most mature of the young women at the paper. She had lived alone for many years, as her parents worked overseas. She was much more independent-minded than most young people in Vietnam – who generally live with their parents at least until marriage. My Ha was planning to attend the Columbia School of Journalism in the Fall, if she could raise the money or get a scholarship. She was determined to go, despite the incredible cost.

It was about this time that Hari finally arrived. Phuc also lectured him for being late. I ate a bit more food from My Ha’s table. She and Hai Van were so busy talking they had eaten very little. When some energy returned to me, I went over to the table where the layout team was seated. Most were young men who had day jobs and would come to the office around 7:00 pm, to work straight through until midnight. As the World Cup was on, I knew the Spain-Portugal match would be the main topic of conversation. I talked with one of them, Linh, about the bets he had made. He told me most of the guys were in serious debt from gambling – and the first round had not even ended.

When my knowledge of football was exhausted, I went back over to the table where my foreign colleagues were sitting. As soon as I did this, people began heading to the small stage at the front of the room. As at any Vietnamese party, the highlight was the opportunity for everyone to sing. First to the stage was Thanh, one of the layout staff. He was followed by My Ha, and an older woman named Mien, who sang in Russian. Khuyen also sang, and his wife danced. Some of the older staff members sang revolutionary songs. Hari sang a song in his native Malayalam. He went on for several minutes, and when the song threatened to continue indefinitely a boisterous Australian man I had not seen before, complete with oversized bush hat, walked to the stage and stood next to Hari, glancing at his watch. John Loizou, after much persuasion, came up and sang an Irish rebel song. He then demanded to know why we had not yet heard a Canadian song. ‘I’m very sorry, I love you all very much, but I don’t sing,’ was my pleading defense. I was saved because some of the other foreign staff members went up to the stage. Bob, an enormous man from Alaska, sang a Native American song. Jon, a young, reserved American, then sang a Swedish drinking song about frogs. He translated the ridiculous lyrics, to much laughter. Finally, a young man named Hieu gave a touching speech about teamwork at the paper, followed by a rousing rendition of ‘Yellow Submarine.’ Everyone sang along, myself included.

After the singing was over, tables were cleared away and lights dimmed. The hotel began playing some old disco music, of the sort popular in Vietnam. Boney M, or something similar. Hari requested Bob Marley, but the DJ had never heard of him. Most of the older staff went home, but all the young Vietnamese staff, as well as Hari, John and myself, stayed to dance. John was quite drunk. I tried to drag Van Anh out to the dance floor, but she was very nervous. She wanted to dance, but said she didn’t know how. Eventually I pulled her to her feet and held both her hands. She wouldn’t move her feet, so our dancing was limited to me swinging her arms back and forth. ‘Move your feet!’ I kept imploring, and she would take a half step to one side.

The dance party only lasted thirty minutes or so, and then the hotel turned on the lights and tried to stop the music. Everyone pleaded for a few more songs, but eventually the staff pushed us out the door. The escalator had been reversed so people could ride it down to the lobby, but when I left the hall there was already a small group of my female colleagues standing just before the escalator, too scared to hop on. None of them had ever been on an escalator before, so they were trying to grab the railing and step directly onto the moving stairs. They would lift one foot, then pull it back in fear when the stair moved out from underneath them. Hari was watching this and laughing hysterically. One after another the women stared intently at the moving stairs, one foot in the air, trying to find a safe place to put it. Hari was taking photos, and I tried to physically push Hai Van unto the stairs. She resisted, until Thuy Ha took a daring leap forward and suffered no harm. One by one they jumped on, and I walked on with Van Anh in tow.

In the lobby more photos were taken and My Ha sat down at the baby grand piano in the lobby bar. Soon everyone was quiet, listening to her skillful playing. John sat close to her in an alcohol-induced trance. After a few songs she got up from the piano to great applause. We moved outside and people began to discuss where to go next. The heat was still oppressive, so I suggested going for ice cream at one of the nearby cafes next to Truc Bac lake. A few people decided to go home, but about twelve of us, including John, went off to the café. We crowded around a small table and ordered drinks and ice cream. After everyone had finished, I offered to pay, and went up to the counter. I did not normally have the opportunity to take my colleagues out, but with my salary this year much higher than in 1995, I knew it was the least I could do. When the waitress gave me the bill, I looked it over quickly and brought out my wallet. Thuy Ha then pulled the bill from my hand and began counting it herself. She wanted to make sure I wouldn’t slip up. She counted twice and decided the café had undercharged us by 2,000 dong. She wrote the new total, and I protested at her costing me more money. I tried to explain that you only check a bill to make sure you’re not paying too much. She didn’t seem to care. After this, everyone said their goodbyes and got on their motorbikes.

As I biked home after the seventh anniversary party, I found myself weighed down by mixed feelings. I wanted out of the Vietnam News, desperately, but I recognized I was lucky for the opportunity Khuyen had originally given me in 1995. I came to Vietnam to learn, and being a frustrated staff member of a government organization was one of the best ways to gain insight into how the country worked, and how so many seemingly average people maintained their integrity in the midst of a society so rife with corruption and inequality. My Vietnamese colleagues were wonderful people, and their patience with us was far greater than the patience we displayed in return. They had such loyalty to the paper, and to Khuyen, that I felt guilty for often belittling their efforts in talks with my foreign friends. I really did treasure the opportunity to attend events like the paper’s seventh anniversary. I just didn’t want the dull routine that came in between the parties.

9.

In late November of 1998, I told Khuyen I was leaving the paper. I had finally secured a job at a development organization – a small local group that work in the highlands with ethnic minorities. I told Khuyen I had originally come to Vietnam to work in the countryside and prepare for my PhD, and now I had the opportunity. He told me I would be missed, and wished me luck with my new job.

I was living at the time with a Canadian man named Julian Wainwright, who also worked at the paper. We lived next door to two other Canadian women, and were surrounded by a circle of young Westerners who liked to have fun. Work long ago had taken a back seat to going out at night and spending a lot of money on food and drink. Mostly drink. It took me a long time to find the type of job I wanted, at a Vietnamese development organization working in the highlands, and when the offer finally came, I was in the mood to celebrate. Julian, having worked at the paper for several months, understood exactly how happy I was. In fact, I had decided that if I did not get a new job by December, I would return to Canada empty-handed. As it turned out, I just beat this deadline. I got back to Ottawa on Christmas morning, and ended up staying in Canada for three months as visa details were worked out to return and start my new job. I knew that when I got back, Julian and several of my other friends would have left the city. Life in Hanoi would be a lot less fun. But this didn’t worry me, as I was starting over myself, at a job that was very important to me. I was relieved that I had finally closed the door on the Vietnam News. My life as a cadre was over.

10.

I didn’t see Khuyen again for well over two years, until just a week before I left Vietnam in June 2001, after working for almost three years at a local non-governmental agency. I called my former chief editor and told him I was writing a book. When I said the first chapter was about the Vietnam News, he laughed and asked if there was much of a story to tell. I said I wanted to reflect on how we coped with such a multicultural office, and ask him about what he felt the paper accomplished. He agreed immediately to the interview, and told me to come around his house on a weekend morning. When I went to his house, I found a different man than the one I knew at the office. He was relaxed and friendly, looking fit and trim, waving to me from the top of the stairs that led to his living room. We exchanged pleasantries and he told me how he had gained four kilograms within one month of retiring. Clearly, the stress of the job had affected his character, which might explain why I considered him somewhat dour during my time at the paper.

By this time I had interviewed several former staff members, and I had gained a greater appreciation for how hard Khuyen worked to make the paper a success. I also learned that Khuyen had a much more independent mind than I previously thought. Khuyen was from an elite Catholic family in Hai Phong, and his father died in factional fighting early in the revolution. Although Khuyen himself sided with the revolution, there were clearly doubts in his mind that all the new leaders of the country were the right people for the job. He did not join the Communist Party until late in his career, while he was in Cambodia, when he heard about the doi moi reforms and the changes they promised.

As one former staff member told me: ‘He was on a mission – to stick it up the noses of the new order. He wanted to show the VNA stiffs there was another way to run a newspaper without being anti-patriotic or anti-Communist Party. That’s why he hired a lot of foreigners, just to have the diversity to appeal to different people.’

Khuyen recalled the early days of the paper with obvious fondness. We had greater initiative than at VNA,’ he said. ‘We were a pioneering group, and the team spirit was very strong – we wanted to be competitive with VNA and the local papers. We sent people out to get stories, and look for new collaborators in government departments. We had a scoop almost every day.’

The move from the VNA office to 79 Ly Thuong Kiet was made because ‘without the spirit of competition we wouldn’t make much headway.’ When I mentioned the other English-language media, the Vietnam Investment Review and the Vietnam Economic Times, Khuyen says he never felt they were competitors. ‘VNA was the competition,’ he said – despite the fact that the Vietnam News was, strictly speaking, a VNA publication.

Khuyen made headway in many areas, including the roles given to foreign staff members. Terry Hartney was hired as a journalism trainer, one of the first Westerners in Vietnam to have such a position. There was a joint venture with a Thai company that also broke new ground for VNA, and it helped the Vietnam News grow quickly into a profitable paper. For many years, the only VNA publications that made money were the Vietnam News and a sports publication called Van Hoa-The Thao. The Vietnam News did so well it helped keep VNA afloat. One younger staff member told me, ‘Our salaries are so low because we have to support somebody else.’ As she said this, she pointed suggestively down the street towards the VNA office. The Vietnam News was also one of the first Vietnamese papers to go online. Khuyen says the bulk of mail received by the internet edition was positive, save for some protest letters by overseas Vietnamese groups in California.

Khuyen’s approach of relying on youth over experience was also refreshing, particularly for a government office. ‘I was very selective – but open-minded – in my attitude towards young people. They had a chance to prove themselves, and I don’t remember if I ever said no to a young person who came (directly) to me and asked for an apprenticeship.’ (This in a country where many state jobs are procured through nepotism and cash bribes.)

When it came to foreigners, Khuyen clearly did not have the best and the brightest to choose from, and he made some mistakes. However, he maintains that even here he was not as haphazard as I once thought: ‘I know a carpet bagger when I see one,’ he told me. ‘Many people were turned away at the door.’ He mentioned, as an example, that media magnate (and carpet-bagger-deluxe) Rupert Murdoch once tried to buy the paper.

The internet edition of the paper was not the only forward-looking move by Khuyen. He also joined and helped form a Southeast Asian news group that exchanges stories among newspapers around the region. Some staff members have gone to the Philippines and other countries to apprentice as journalists. The staff members who went to the Philippines were grilled about how limited their skills were, and they got a good taste of how real reporters operate. Another young staff member also apprenticed at a paper in the United States, while others went to Thailand.

Clearly, the progress Khuyen made does not look all that radical for people who want to see a much more open media emerge in Vietnam. Although he allowed foreigners to voice some complaints in letters to the editor and other columns, he did not stand for anything with even a hint of subversion. But despite walking the official political line, he still clearly made it difficult for the people running VNA. As he says, ‘We didn’t rely on VNA for anything,’ and he never attended the weekly VNA meetings where stories were reviewed and plans made for the upcoming week.

There is some speculation about the timing of his retirement. At first, VNA asked him to stay on past the normal retirement age of 60. He stayed for three extra years, then left very suddenly, almost overnight, on November 1, 1999. I suppose he must have found a way to retire on his own terms.

The day after he left, Terry Hartney wrote a farewell to Khuyen in the paper. In the headline, Terry called his boss ‘Mr. K’ – a nickname I began using in 1995 and which by then was employed universally in the office. Terry wrote that on the day of his retirement, an unknown European man came to the office hoping to meet Khuyen. When told Khuyen was not there, and that he was not working anymore, the man said, ‘That is a serious loss. He’s the best editor I’ve ever met.’ The stranger then left, without telling anyone who he was or how he knew Khuyen. (Soon after Mr. K retired, Terry was ‘phased out’ by VNA. They told him they did not want a foreigner training Vietnamese journalists.)

At the end of our talk, Khuyen almost made me forget how much I disliked editing the new briefs at the paper. The wider context of the Vietnam News office in the mid-90s – a room full of a seemingly random collection of Western misfits, young and enthusiastic Vietnamese beauty pageant contestants, and older Communist Party intelligentsia, all coming together to bang out some semblance of the fourth estate – was a never-to-be-repeated opportunity and environment. Khuyen said he no longer had any contact with the paper, although younger staff members sometimes dropped by his house for small parties. He seemed very content to have the time to catch up with family and old friends. ‘Is it egotism,’ he asked me, ‘to like being myself?’ I asked him to name his major accomplishment, and he again replied with a question: ‘Can I say that I retired at the top of my profession?’ It sounds like an overstatement, but in Vietnam only a few brave people challenge authority or the status quo in any manner. Khuyen did this, with the careful, subtle approach of someone patient enough to note progress word-by-word. Definitely the mark of a great editor.

11.

The tenth anniversary party of the Vietnam News was held the day after I left Vietnam in 2001. I was invited, but decided not to attend. My visa expired the day I was due to leave, so staying for the party would have been difficult. Regardless, I didn’t feel the need to go. I had met up with most of my former colleagues during the preceding two months. Two and a half years after last stepping into the Vietnam News office, I turned up one night and talked to the deputy editor who worked the night shift. He was a very conservative man who meddled with any story that had even the most remote possibility of causing offense. I told him I was writing some stories about Hanoi, and wanted to look through old copies of the paper. I didn’t tell him I was writing a story about my time at the paper. He asked me to write an article for the tenth anniversary edition of the paper, and I agreed. But after a few nights of reading old issues, I got what I needed and no longer dropped in at the office.

I didn’t see the new deputy editor until a few days before I left. I had already interviewed Khuyen. I went to the Vietnam News office one last time, to say goodbye to some of the staff members. When the deputy editor saw me, he was clearly annoyed I had not written an article, as promised, for the tenth anniversary edition. Originally I had planned to write a reflection about my time at the paper, based on my notes for this very story. When I looked everything over, I realized I had nothing suitable. At least nothing the new regime would be willing to print. I suppose if it was Mr. K who had asked me to write a piece, I would have tried a little harder.

A visit from a man who claimed he was robbed at gunpoint and his secret documents stolen.

Richard Pettit was the Charles Bukowski of Hanoi in the late 1990s. This is one of his stories.

Funny cartoons about air raids, forced conscription and ration tickets.

© 2017 Michael L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy